The Rise of Solarpunk Or ‘How Muriel Jaeger’s ‘The Question Mark’ led me to Solarpunk.’

(Long Read)

SolarPunk. A term you may come to know well over the next few years, but what is it? I first stumbled across this term early last year, and that really was what it was, a stumbling. I had started work on a body of work I’m hoping to release in the next year or so and couldn’t quite put my fingers on what it was I was creating. Finding this term tripped me up enough to stop me in my tracks and breathe a sigh of relief.

If you’ve heard early episodes of the podcast, you’ll have heard me talk about my own partiality towards dystopian literature. Since my teens I’ve been fascinated by the works of writers like Ira Levy, George Orwell, and Philip K. Dick. I’ve always found it easy to envision a world without human beings and to daydream what might happen if the electricity (and now internet) went down and we lost all connection with each other. As a child, with my mum driving us to visit my Auntie in nearby Guildford, I would imagine the road with no cars, the tarmac cracked and rutted as nature slowly reclaimed these paths.

This relatively early exposure to these dark and futuristic worlds inevitably had an impact on my writing, especially during my thirties as I slowly returned to the page after a lengthy absence brought on by a stressful teaching career and early motherhood. Each time I wrote, every world I created seemed to have been plucked straight from the pages of 1984, This Perfect World and Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (though admittedly with less literary finesse and academic insight). I couldn’t put my finger on what it was but seeing the world as it might be in the future came to me as naturally as breathing.

A couple of years ago, I started working on a piece of writing - which never really went anywhere in the end but which you can read here - using one of my own prompts. What began to emerge was yet another peek into an as-yet unseen world of the future. To summarise, it was about a commune of people living in some undetermined time in the future and explored how society might be rebuilt following its collapse and ecological breakdown, all told through the lens of the rights-of-passage journey undertaken by a young person. The work was never finished because I realised that, for my own mental health, I couldn’t keep writing about the darkness I felt was coming.

For context, my work with the Benfield Valley Project, and everything I’m learning about town planning and land management here in England means that I am constantly immersed in a world of ‘biodiversity net gain’ and having to listen patiently to people who know nothing about the land make decisions about the green spaces that support local communities. Additionally, working with Parents for Future means I see just how hard it is to make change. Whilst writing in this style, these frustrations interspersed with my life and I realised I couldn’t keep internalising all this grief, sadness and anger to the point that it was coming out in my creative work. Coming out in my morning pages or free writing, which no one will ever read and helps me to make sense of it all, maybe, but not in my wider creative work; I needed to look ahead and see something other than tarmac and fossil fuels, to move beyond a monochrome world of greed and inequality and the solipsism of the modern world. My heart, mind, body and soul desperately needed me to look forward, to alchemise this grief and see something different, to begin to envision a world I actually wanted to live in, a world in which I wanted my children and their children to grow up. I needed to pick up my pen and see it as a multi-coloured paint brush, to see the blank page an easel onto which I could streak every colour and shade in the other-than-human world and create something completely different. In essence, I needed to push my own writing forward and stop buying into eco-doomism.

*

Finding ‘The Question Mark’

It was soon after this that I visited a little bookshop whilst visiting my Mum in the West country. It’s one of my favourite book shops run by just one woman - the kind of person who knows everything about every book she sells and always convinces my children to spend their pocket money on books about witches and the natural world, (which I’m never against, by the way). On this particular day, I came across a book called, ‘The Question Mark’ and was immediately intrigued: A speculative fiction book, written by someone other than a man, about a utopia of the future - it felt like exactly the kind of thing I needed to be reading so I gave it a go.

Written in the 1920s by feminist writer Muriel Jaeger, the book is a vision of a world 200 years in the (her) future - 2120. It is a world in which money and the need to work no longer exist, a world in which humans can flourish as humans and are encouraged to pursue art, literature, whatever comes naturally to them.

My optimism was short-lived however as it soon became clear that his was just a regurgitation of everything that already existed at the time of writing: sexism, elitism and the freedom of the privileged at the expense the marginalised (though these are redefined in the book as ‘intellectuals ‘and ‘normals’). What begins as a ‘utopian’ vision of the future quickly becomes a dystopian reality for the protagonist, a man from Jaeger’s present.

In a way, I can kind of forgive Jaeger’s lack of insight and revolutionary thought around gender simply due to the time in which she was writing: feminists were concerned with women’s rights and emancipation, not the questioning of gender altogether - which we might expect now - and she may not even have been aware of any questions; we don’t know what we don’t know. What I can’t get my head around though is why, if she was envisioning a utopian future and was immersed in feminist thought and activism, women are still just seen as tools, not being ‘adults’ until they were married. If she had enough imagination to create a world without money and work, why could she not imagine a world in which women were seen as human beings? Perhaps that’s the point though, she either couldn’t see a world free from the stranglehold of patriarchy, or could, but didn’t think it was possible.

‘The Question Mark’ had touched on something I needed to be reading but, for me, it still relied on dystopian tropes, largely dominated by latent patriarchal ideologies. The imagination and creativity I craved just wasn’t there. In This Perfect World, Levy got closer to it, but still ended up suggesting that humans, if left to their own devices, would descend into chaos and conflict. It was at this point that I started searching and researching. There must be others writing in the way I craved, artists and creatives by whom I could feel inspired.

*

Enter the ‘Solarpunk’

Then somehow, somewhere, I fell across the word ‘Solarpunk’ and found myself taking a deep sigh of relief. There it was. A word that perfectly described in just nine letters the world of which I wanted to be a part.

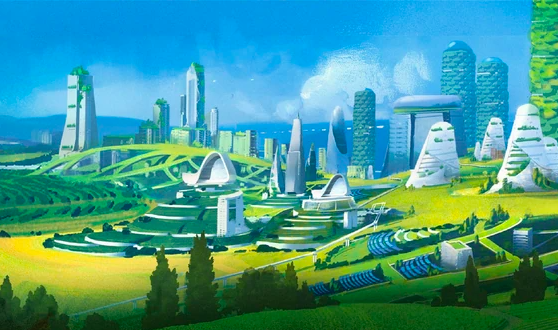

If you Ecosia it, Solarpunk is described as an aesthetic movement concerned with envisioning a truly sustainable, ethical, equal world in which life - human and other-than-human - is respected. Solarpunk magazine defines it as, ‘a prefigurative, utopian artistic movement that envisions what the future might look like if humanity solved major modern challenges like climate change, and created more sustainable and balanced societies.’ (Issue 1, see resources and articles below for links)

As a genre, Solarpunk takes a radical look at the ways in which we can live with and alongside nature, building resilience and using technology as an ally rather than a destroyer, or diminisher, of life. I’m learning too that it is so much more than that. It is an opportunity to question absolutely every aspect of our lives and societies - gender, architecture, health, family and community, leadership and governance, gardens and green spaces, food, work, money, spirituality, climate breakdown, relationships…you name it.

I started to notice that, without realising, everything I had been doing for the past few years - working to protect and celebrate a local green space, mentoring young people at work, environmental campaigning, creating podcasts exploring the intersections of nature and creativity - had become informed by the ideals of Solarpunk, even though I hadn’t even known that the word existed.

The Potential of Solarpunk

If I had to, I would now describe myself as a Solarpunk, though I know that in labelling myself, I must acknowledge the fluidity and transience of labels; that they can change as I change and to label myself stridently with one things risks putting myself in a pigeonhole I can’t find a way out of. But that’s the beauty of a movement like Solarpunk and its younger sibling Lunarpunk, both invite us to question and to keep questioning; to keep pushing oneself to envision and, more importantly play a part in creating, something more constructive than the world we find ourselves in now.

In all honesty, nothing else as a genre makes sense to me right now and I can’t help but wonder about what it would be like if children and young people were taught about solarpunk in schools. What if it became a discrete subject, a topic area that could inspire the content of every single subject? How could its art, science, literature, inspire generations to come.

Solarpunk fills me with hope and optimism: the two things I was looking for in those futuristic worlds I found myself creating for all those years. It is a destructive force in the most beautiful, transformative, sense of the word: it questions everything you know, asks you to destroy it and then, through its art, literature, music offers you the opportunity to rebuild it from the ground up. Solarpunk invites us all to explore with audacity and courage, the deepest recesses of our imagination and pluck out the kind of possibilities we only see in the films or read of in books; the kind we feel may be impossible until we try. It is creativity, collaboration and connectivity in their purest forms, centring those most marginalised in capitalist systems and using their stories to construct a world with equity and compassion as its foundations. It is where we humans need to put ourselves if we stand any chance of survival.

At its core is a movement that makes me feel less alone. This subgenre is not a bandwagon on which to jump, it’s a total revolution of thought that includes everyone. Once you know Solarpunk exists, you cannot, and will not, unsee it.

Fancy using Solarpunk as a writing prompt? Go here for some inspiration.

*

Resources and articles:

https://solarpunkmagazine.com/ - a hugely inspiring bi-monthly magazine exploring the issues, intersections and imaginings that come from the Solarpunk genre. Offers subscriptions and one-off purchases. They also have a Patreon and a podcast, ‘Solarpunk Futures’.

https://solarpunkmagazine.com/9-reasons-why-solarpunk-is-the-future/

https://republicofthebees.wordpress.com/2008/05/27/from-steampunk-to-solarpunk/ - the article credited as being the first use known of the term ‘Solarpunk’